The Soviet government’s attitude toward how much western influence was allowable seems rather arbitrary. For example, “Even during the years when jazz was under extreme attack Soviet orchestras occasionally played jazz tunes that were arranged in the style of Soviet “light music,” changed their names, inserted them among Soviet compositions, and, in these reinterpreted forms, jazz continued to be heard in restaurants and dance halls, and occasionally even at the concerts of state philharmonic orchestras” (Yurchak, 167). One Soviet jazz lover put his feet up on his chair while he listened because “‘American music must be listened to in the same way as it is listened to in America'” (Yurchak, 168). Later in the country’s history, “newspaper articles also reminded their readers that any Soviet person who aspired to be “‘cultured … should be fluent in one or several foreign languages’… as long as one learned the right information and did so with a critical eye” (169), and “Nikita Khrushchev publicly ridiculed Picasso’s abstract art displayed in an exhibition at Moscow’s Sokolniki Park for its bourgeois lack of realism. In May 1962 however, Picasso was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize for the progressive internationalism of his work as a Communist artist” (165). Due to this, it is little wonder that many Soviet citizens thought of the west as imaginary, like a place you can never truly understand until you go there. By the 1970s, ordinary people were creating their own western-based art without so much fear of the government. Was the regime’s refusal to unequivocally condemn western culture based in a desire to make it less attractive as a forbidden fruit, or the knowledge that the Soviet Union had to stay on some level with the rest of the world?

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- isgray on Pussy Riot and the Western gaze

- gisherzfe on Russian Cynicism and a Basket Case Mentality

- isgray on Shared Histories and Populism

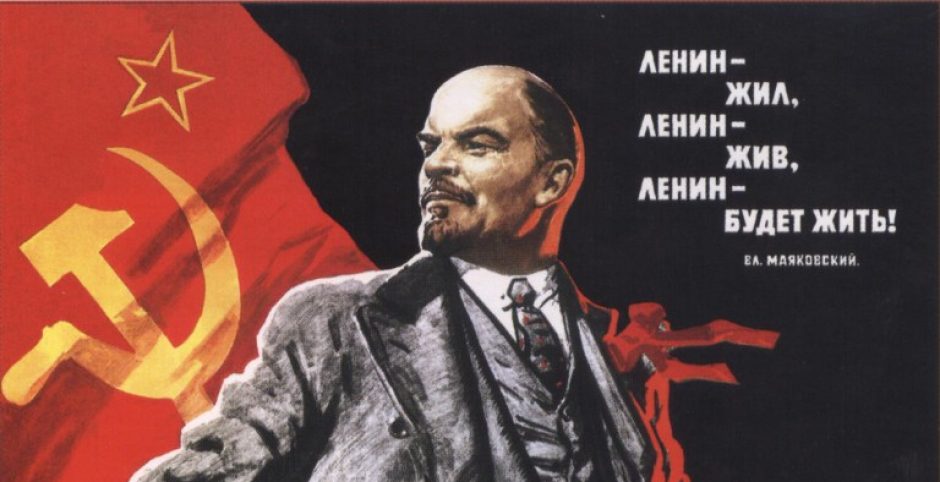

- gisherzfe on National trauma and the cult of personality

- wolfsje on National trauma and the cult of personality

Archives

Categories

Meta

I think that what was occurring was a conflict of ideology and practice. Much like the period of de-Stalinization, the party had to make a compromise between the original tenets of Communist ideology and the governing tactics that kept the USSR together. In this way, the party wanted people to become world citizens by listening to foreign broadcasts as the eventual goal of the USSR was to spread beyond its borders and bring Communism to proletarians around the world. There is a quote about this a little before our reading starts that states “Zhdanov’s argument can be summarized as follows: foreign musical in influences could represent bad cosmopolitanism or good internationalism…” (Yurchak, 164). However, the party also had to, and did, eliminate the most potentially subversive broadcasts to its power, done by blocking certain bands of transmission.