Once in power, Khrushchev’s response to Stalin’s death and the subsequent confusion surrounding it was, increasingly, to control the memory of the Soviet Union’s late leader. As Jones details, the years between 1956 and 1961 saw a shift from “‘correcting’ iconoclasts to viewing them as potential ‘enemies'” (Jones, 51). Verbal participation in de-Stalinization was still acceptable, but physical participation was not. And, even in verbal criticism, “discussion was closed off” (59). Personal tales of suffering under Stalin were to be the product of Stalin himself – not the Soviet system.

The death of a leader such as Stalin, whose cult of personality “trained [Russian people] to believe that [he] was taking care of everyone” (Evtushenko), marked the end of a particular social order and an opportunity for dissent. Thus, while Khrushchev might have sought to ‘de-Stalinize’ and liberalize the USSR (in very relative terms), he also sought to defend the Soviet system upon which his power depended. By forming a “clearer script about Stalin” (59), Khrushchev and his party could control public opinion and suppress dissent.

This makes me wonder – how might one denounce or criticize Stalinism but not the Soviet system?

And what threat did Khrushchev perceive that might have influenced the Party’s approach to de-Stalinization?

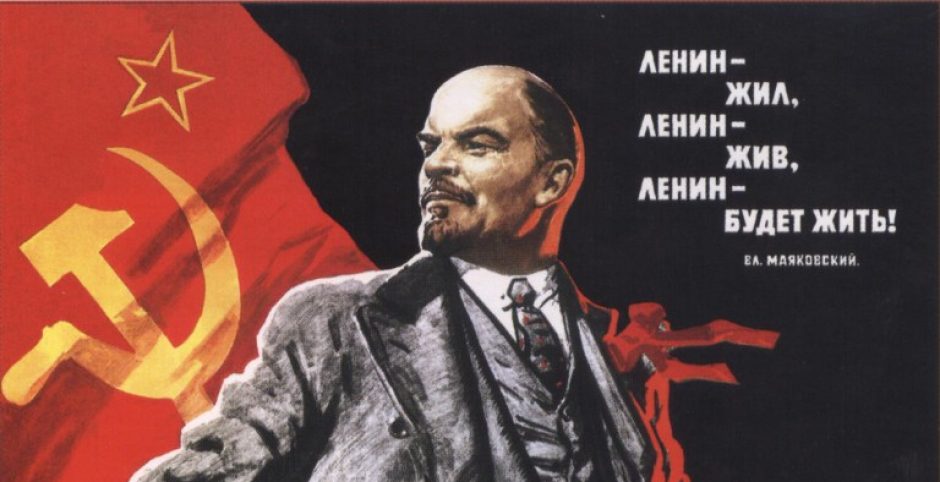

I think that Khrushchev went out of his way to criticize Stalin as an anomaly, a corruption of the traditional Leninist foundational principles of the Soviet Union. The official dogma that surrounded de-stalinization (and the kind of rhetoric that was used throughout the speech) was very ‘while Lenin did x, Stalin did the antithesis of x, and y and z as well’. Take for instance the laundry list of grievances in the Secret Speech – “Lenin used such methods, however, only against actual class enemies and not against those who blunder. Stalin, on the other hand, used extreme methods and mass repressions at a time when the revolution was already victorious.” or “. Lenin always stressed the role of the people as the creator of history. Lenin mercilessly stigmatised every manifestation of the cult of the individual. Lenin never imposed his views by force.” – which both set up the implicit contrast between the ideal Leninist and the shameful Stalinist. In this way I think that Khrushchev could critique the Stalinist cult of the individual without scuttling the Soviet system he depended upon.

Another thing that caught my eye was Evtushenko’s description of the Russian people’s view towards Stalin – as a protector, as someone who “[had] been an indispensable part of life.” The rhetoric he uses and the way in which he describes the shock resounding throughout the USSR makes me wonder about the inevitability of the formation of a cult of popularity surrounding a strong leader. I feel that because of the long national tradition of autocrat-worship, and the peasant belief that the Tsar was their most prominent protector, a similar situation occurred in the communist phase. Evtushenko addresses the problem of belief, saying of the Russian people that “For them ‘living’ had always included ‘believing”. Perhaps this belief lies beyond the foundations of the Soviet Union, and stretches back into the character of Russia that Evtushenko addresses.